INSP editor Tony Inglis: “If football cut out corporate greed, it could learn something from the solidarity of the street paper network”

By Tony Inglis

- Journalism is not a crime

With soccer on the mind due to the imminent Homeless World Cup in Sacramento, California, INSP editor Tony Inglis writes about the rise of “multiclub” networks and how, if state-subsidised wealth and corporate greed didn’t poison it, the sport could learn something from how street papers have historically been connected.

As a passionate football fan, this time of year – when there’s no major international tournament – can feel a bit barren. But that’s just when you focus on the professional game. With the Homeless World Cup ongoing from 8 to 15 July in Sacramento, it will valuably scratch that itch.

Of course, the work of the Homeless World Cup in improving the lives of people living in poverty and experiencing marginalisation makes the glitz, glamour and depressingly money-driven professional game look a little silly. Add in how street papers have contributed to this history, and even your local team begins to look vacuous.

Last week, Rory Smith, The New York Times chief soccer correspondent, reported on the rise of “multiclub” – the practice of larger, sometimes oil money-rich, clubs buying up smaller clubs abroad creating a kind of global club brand. For anyone with an eye on the game, this will not be a new phenomenon: Manchester City already has multiple from Australia to the USA and India, and they simply followed on from the Red Bull model in New York, Leipzig and Salzburg.

The Argentinian street soccer team, supported by the Argentinian street paper Hecho en Bs. As. Courtesy of Hecho en Bs. As.

In his report, Smith wrote: “Owning a network of teams should allow owners to share best practices more easily while reducing risk and increasing efficiency in the transfer market. A network should, if constructed correctly, function as a two-way talent pipeline: The best players rise to the top of the pyramid, while those who fall by the wayside have landing spots farther down, meaning there is far less waste. Collective safety offers a degree of economic stability. It may even, at some point, give them access to a higher calibre of player than they’d otherwise get.”

As Smith goes on to write, “that is the theory. The practice is a little different.” Money and power has flooded the professional game to the point that the community values that many football clubs were established under have dissipated. As Smith writes, “the trend represents something significantly more troubling: not so much an inevitable conclusion to the sport’s flirtation with high finance but something far closer to an existential threat.” Smith seems sceptical about its efficiency as a model within the current strictures of the sport.

It made me think, what could a network look like devoid from corporate power, greed, hierarchy, competitiveness even, and instead predicated on things like cooperation, collaboration and solidarity? It feels like such pie in the sky at this point to imagine it.

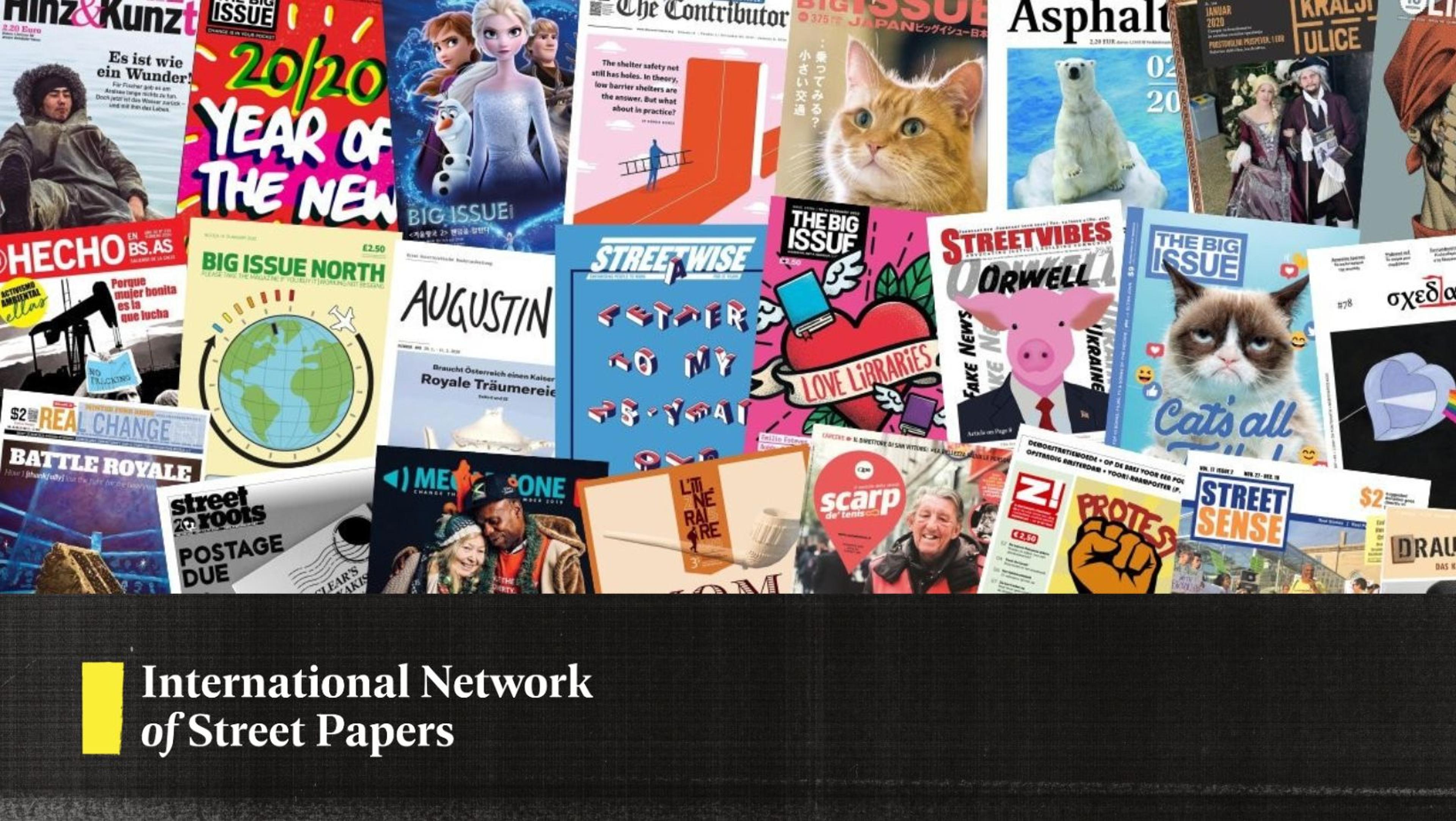

What could a network look like devoid from corporate power, greed, hierarchy, competitiveness even, and instead predicated on things like cooperation, collaboration and solidarity? It turns out I didn’t need to look too far for a comparison. The street paper network is a unique model, a far cry from the cash-lined corridors of modern football

But it turns out I didn’t need to look too far for a comparison. The street paper network is a unique model, a far cry from the cash-lined corridors of modern football for sure, but also a far cry from its borderline anti-moral stance on carrying out business, one that is soft in the face of bigotry, cyclically rewards the wealthiest teams, and is not afraid to deal with nefarious businessmen and troubling regimes.

Street papers have existed as a network for nearly 30 years, and while they are diverse in form and tone, and don’t always agree, even its most opposite poles continue united. The largest among them continues to do its best to help benefit those with least resource. The ones who have innovated willingly share best practice. None encroach on the work of another. And every two years they come together in celebration. Perhaps there is a future where the mainstream learns from their example.

Support our News Service

We believe journalism can change lives, perceptions, and society - underpinning democracy for a more equitable world. Learn more about the INSP News Service and how to support it here.

You may also be interested in...

INSP editor Tony Inglis: “Martin Scorsese’s new film shows co-creation alongside people with lived experience can change the narrative”

Read more

INSP North America director: “Street papers believe in the idea that journalism can bring people together to make the world we live in a better place”

Read more