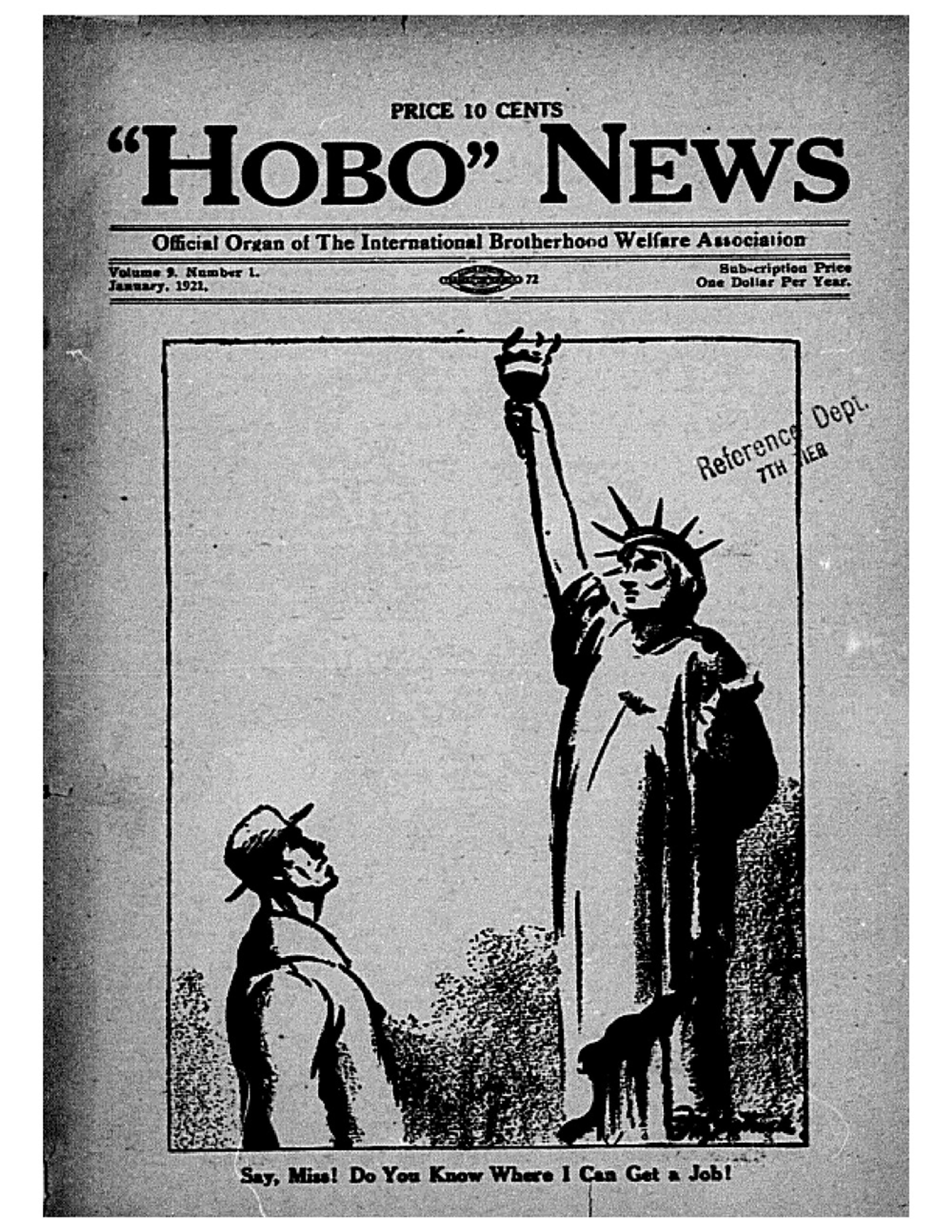

Hobo News: the first street paper?

Hobo News, Courtesy of Dr Owen Clayton

Article by Dr Owen Clayton

- Opinion

Between 1915 and 1925, the International Brotherhood Welfare Association in Chicago, US published the “Hobo” News, the world’s earliest known street newspaper. Like many subsequent papers, it provided subsistence by allowing vendors to keep a portion of the proceeds.

On 12 April 1923, 200 Chicagoans attended a public debate, chaired by the notorious sex-positive “clap doctor” Ben Reitman, between three university students and another trio who identified themselves as “hobos”. The question was whether Kansas ought to establish a court to mediate industrial disputes, with the university students arguing in favour and the hobos against.

We know of this event thanks to an account by one of the debate’s three judges, the hobo-turned-sociologist Nels Anderson. According to Anderson, the students were long-winded and “presented their arguments in the usual conventional manner”, which left them “unable to get the ear of the audience”. Their main argument was that US institutions could be trusted to adjudge industrial disputes fairly.

The hobos, by contrast, spoke of their real-world experience of being in front of American judges. They spoke of going to prison for violating so-called “Tramp laws”, which criminalised poverty by making it an offence to cross State lines “without visible means of support”. For these men, judges were a class enemy who could not be trusted.

Anderson describes the three hobo speakers as being logical, well prepared and “caustic”, especially a man called John Laughman, who “was humorous and terrible by turns”. Laughman in particular was used to public speaking, being a regular participant in open-air debates held at “Bughouse Square”, just in front of Chicago’s Newberry Library. The hobos won the debate, winning over two of the three judges, presumably (though he does not say so explicitly) including Anderson.

This debate took place in Chicago’s “Hobo College”, which was one of many institutions run by the International Brotherhood Welfare Association (IBWA), an organisation founded by the “Millionaire Hobo” James Eades How. These colleges provided accommodation and free education for transient workers, or, as the IBWA, called them, hobos.

Though it predated the IBWA, Eades How’s organisation aggressively campaigned to privilege the term “hobo” over alternatives, such as “tramp” or “bum”. They adopted Dr. Reitman’s distinction that “[t]he hobo works and wanders, the tramp dreams and wanders and the bum drinks and wanders”.

One reason for making such a distinction was to avoid the legal consequences of being called a tramp. Another reason was because, in a context in which US transients were demonised as, at best, lazy and feckless, and, at worst, dangerous to women and society more generally, the IBWA sought to reframe its members as hard-working Americans. It was hobos, the IBWA proudly asserted, who built up the American West following the closure of the frontier around 1900, working in lumber camps, mines, mills, railroads, harvest fields and other places.

Key to this campaign was the “Hobo” News, which the IBWA launched several times but the most sustained publication run of which was between 1915 and 1924. The “Hobo” News is the world’s earliest known street newspaper. Like many subsequent papers, it provided subsistence by allowing vendors to keep a portion (in this case, half) of the proceeds.

The hobo vendors did not just sell the paper: they also wrote for it. Around 80 different transient contributors wrote for the paper, providing news articles, short stories, poems, comic “society news” pieces, and even a parody version of an agony aunt. This allowed the “Hobo” News to brag that it was “OF THE HOBOES, BY THE HOBOES AND FOR THE HOBOES”.

This pioneering model was hugely successful, with the paper selling 20,000 copies per month at its height. There were even international vendors selling the paper in Japan, Sweden, Scotland, Ireland, and England, and an (unsuccessful) attempt to establish a London version of the Hobo College.

The material on the pages varied over time, and there were battles as to what kind of paper the “Hobo” News ought to be. Some favoured accounts of lived experience, while others sought to make the paper into a pro-Soviet propaganda organ.

Though clearly written with a male audience in mind, its representation of women improved over time, not least when Eades How appointed a female editor, Laura Clarke. Unfortunately, the paper lacks any representation from transients of colour, and some articles display the dated racist humour of their day, though its pages also contain debates about how strong an anti-racist stance the IBWA ought to take.

The paper advocated many progressive policies, including a living wage and a universal eight-hour workday. Most importantly, though, it provided a platform for a widely despised group of unhoused people to demonstrate their writing talent, humour, and intellectual ability. As the famous author Jack London put it, “Hurrah for the hobo newspaper! I wish there’d been something like that afloat when I was knocking around on the road”.

But calling the “Hobo” News the first street paper may not be entirely accurate. Most papers of this kind from earlier periods have not survived, so it is difficult to know what we are missing. We do not even know when the “Hobo” News stopped publishing. The copies of the “Hobo” News that we do have survived through chance, being kept on open shelves in the St Louis Public Library for decades without the library being aware of what they had.

Other treasures might come to light in the future, changing how we view the history of street papers yet again.

Want to know more? “Hobo” News appears as Chapter 10 of Representing Homelessness, available online.

By Dr Owen Clayton, University of Lincoln